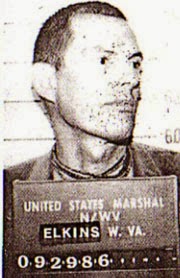

- photo compositing: artist impression - Hansadutta the Isk'Con Rambo

“The Hare Krishnas have got a whole bunch of guns at their headquarters,” a friend on the police force told us. “You’ve got to check them out. They’re really crazy. We checked with a City official. “They’ve got over a hundred weapons up there” he said. “Over 150 weapons,” a police lieutenant said. Shot-guns, AR-15s and .357-magnum pistols.” After receiving these tips we asked a former member of the cult about the Krishna attitude toward violence. “Devotees come to believe that whatever they do is all right as long as it’s done in Krishna s service, he said. “They can even kill if it’s done for Krishna.”

SAN JOSE MERCURY NEWS / JUNE 21, 1987 / WEST

Newspaper Cover Story: How the Krishnas turned bad

By John Hubner

In its early days, the Krishna movement was regarded as everything from a colorful nuisance to a significant link between Eastern and Western culture. But only now are we beginning to learn how deeply corrupt the movement became in less than 20 years. The movement's founder wanted to win the West from its materialism. Twenty years later, his disciples stand accused of running drugs and guns, abusing women and children, and even committing murder. The public, continued to think of the Krishnas as a benign relic of the '60s. Then Steve Bryant’s death stalled investigations that are now going on all over the country. ‘Steve Bryant is a true martyr,’ says Joe Sanchez. ‘He died to clean up his faith.’

THE KRISHNAS TURNED BAD

When HANSADUTTA ARRIVED IN THE BAY AREA in 1978 to become guru of the Berkeley Hare Krishna temple, he told reporters, "To see a big man, you have to see his secretary. I am of kind a secretary to God." Here is how the secretary to God dealt with an administrative problem:

"I called Jiva into my office and held a .38 to his head. I told him he had five minutes to clear out. Jiva turned white and started to beg. I said, ‘OK, you can stay, but you'll have to take a vow of sannyas.’ Jiva took sannyas,"

Sannyas is a vow of chastity, and if any Krishna should have taken it, it was Jiva, an ex-con whose Western name was James Patrick Underwood, Underwood was in charge of the Berkeley temple's women's collecting party, a group of 15 or 20 women who spent every day on the street soliciting money and selling flowers and candles. They were Underwood's harem. He had sex with them, took drugs with them, and beat them. The women were good for $2,000 to $3,000 a day—as much as $10,000 a day during the holidays—but that wasn't enough for Underwood.

"Jiva would drop his people off, and when he came back, the van would be full of suitcases," says Vern Daven, a former Krishna devotee in the Berkeley temple. "He stole them off turnstiles in airports."

Underwood left the Berkeley temple not long after he took the chastity vow. He and a partner began robbing pharmacies, gas stations and liquor stores in Washington and continued the spree into California. They got into an argument near Visalia; the partner shot Underwood in the head and dropped him in an irrigation ditch.

IN THE HARE KRISHNA HALL OF SHAME, UNDERWOOD rates a mug shot at best, Life-size statues are reserved for some of the Krishna gurus. Take Hansadutta (pronounced Hansa-doota), for instance, He is a convicted felon, a former drug addict, a gun freak who stockpiled an arsenal and, one wild night in Berkeley, shot up a, couple of businesses, Hansadutta didn't get into the Krishna movement (formally, The International Society for Krishna Consciousness -- ISKCON) to become a criminal, He joined to become a holy man. j "I had all these questions and no answers, Krishna consciousness was the key that unlocked the answers," says Hansadutta, who joined ISKCON in 1967 when he was a photographer living in Hoboken, N.J., and experimenting with LSD. "The day I joined, I walked out of the New York temple and just started chanting 'Hare Krishna,' I walked all the way across Manhattan, chanting like a lunatic. People looked at me and I thought, 'Go ahead, look. I'm liberated. I have nothing to do with this world.' "

ISKCON is no mere cult that came and went like the one led by Rajneesh, the Oregon guru with the fleet of Rolls-Royces. It is based on a centuries-old Eastern religion. Tens of thousands of people around the world joined ISKCON because in it they found answers to fundamental questions like "What is the meaning of life?" and "Why am I here?" Some were genuine mystics looking for an exotic alternative to Christianity; others were stoned-out hippies from rotten homes who had never had much to believe in. Heirs to fortunes, M.D.s and M.B.A.s joined street people who dropped out of high school. They shaved their heads and put on robes. They handed out literature and solicited money on street corners and in airports; they opened vegetarian restaurants and temples in major cities; and they became part of the American scene, a bridge between East and West.

"The Krishnas helped show America how many ways there are to approach God," says Stilson Judah, a retired UC-Berkeley professor of religion who, wrote Hare Krishna and the Counter Culture," The movement protected our society. It completely changed lives. People who had turned against the establishment found something that was vital and meaningful. They joined and led pure lives.

"The saddest tiling about the movement going bad is that it gave a purpose in life to people who could find meaning nowhere else," Judah concludes. "What are they going to do now? So many have serious psychological problems. It's really, really tragic."

Hundreds of gentle people who want nothing more than a chance to devote themselves to Krishna are still in ISKCON. They are as sincere as true believers in any religion. They joined to live ecstatic spiritual lives, and some will tell you they have. Many others have been through terrible physical and spiritual suffering.

ISKCON is in a shambles today. The movement still claims to have 2 million followers, but religious scholars place the number at no more than 10,000 worldwide. Police agencies in a half-dozen states are investigating ISKCON. In Krishna's name, people have been, murdered, Children have been molested and abused. Women have been brutalized. Sankirtan, the ancient way of spreading the faith by distributing literature and begging for money, has become a springboard for massive fraud. Drugs have been smuggled across international boundaries because of an "ends justifies the means" mentality among some of the gurus. The idea went something like this: "The karmies [the movement's name for meat-eating Westerners] live only for sense gratification, They're going to use drugs, There’s nothing we can do to stop them, so let's make use of this nasty karmie habit for Krishna."

How did a once-vital religion degenerate into a series of competing temples, many of which condone criminal activity? The best way to answer that is to start at the beginning and trace the fall. Hare Krishna begins like a fairy tale in a time of new beginnings, the mid-’60s,

IN SEPTEMBER 1965, A FRAIL, 70-YEAR-OLD HINDU carrying less than $10 got off a tramp steamer in New York City, A retired pharmacist and lifelong holy man, A,C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (pronounced Prab-oo-pad), suffered two heart attacks on the trip from Bombay. He had come to America to start a new religion. The odds on his living more than a year were not good; the odds on his mission succeeding were much worse.

Friends set the swami up in a cheap apartment in the East Village above a shop called, prophetically enough, Magic Gifts, As soon as he was able, Prabhupada was chanting on street corners He chanted beautifully.

Prabhupada preached a Fundamentalist Hindu doctrine that life is an endless cycle of birth and karma, death and rebirth. Karma is a law of moral cause and effect that says the person you are in this life has been determined by thoughts and actions in past lives, Thoughts and actions in this life will determine the type of person you will be in your next incarnation. And so on through eternity,

Prabhupada offered a way out of the cycle, Devotees had to renounce materialism and lead a very austere life—no sex except for procreation, no intoxicants, no gambling, no meat. They had to chant Hare Krishna ("Holy God") thousands of times a day, By living for Krishna and not for themselves, devotees could transcend karma and rebirth and join Krishna in a realm of eternal love called "godhead," or Nirvana. Many forms of Hinduism present an impersonal god, One reason for Prabhupada's success was that he presented Krishna as a personal, loving god, "That appealed to Americans who were reacting against Christianity’s conception of God the Father," says Robert Ellwood, a professor of religion at the University of Southern California. "Here was a new religion that preached devotion to a personal god, but it was an exotic god, and that was fascinating to some people."

Prabhupada had arrived in America at exactly the right moment, Thousands of young people, the "counterculture," were rejecting their parents' values and searching for new ones. So many of them joined Prabhupada, the swami opened a temple in the East Village two blocks from rock 'n' roll's New York temple, the Fillmore. Giant speakers in the temple's windows blasted out the Krishna mantra, Saffron-robed devotees, their heads shaved except for a small topknot, or queue (it’s there so Krishna can reach down and pluck them up to godhead), danced wildly on the sidewalk, beating drums, banging cymbals,

"The movement stressed chanting as an ecstatic devotion that is believed to be superior to the intellect," Ellwood says, "Chanting is supposed to burn away bad karma and everything else, It was presented as a non-drug high, a way to get high and stay high forever,''

ISKCON COMES FROM INDIA, AND ROCK ’N’ ROLL, as the Blasters say, comes from "a howl from the desert, a scream from the slums, the Mississippi rollin’ to the beat of the drums," but the two are surprisingly similar, What is rock but "an ecstatic devotion that is believed to be superior to the intellect"? No wonder Allen Ginsberg, the Grateful Dead, the Jefferson Airplane and George "My Sweet Lord" Harrison all thought ISKCON embodied the wisdom of the ages. So did a 17-year-old named Steve Hebel (Swarup das), "I was walking through the East Village one day in the summer of 1969 when I first saw devotees chanting. I thought, 'This is far out!' " Hebel recalls. "At the time, I really wanted to know, ‘Who is God?’ "

Hebel had first asked that question at age 10, standing over his father's grave. Why had God taken his father away? Inevitably, he began to wonder if there was a God, "God," he'd ask, "if - you are there, change the shape of that cloud," Hebel was a good-looking kid with thick black hair and brown eyes. He was fun, always saying something crazy that broke everybody up. A lot of girls wanted to date him, but none did, "No girls or guitars for me." Hebel laughs. "I was a virgin, into finding the cause of all causes."

Hebel had an IQ that made guidance counselors' heads snap back when they opened his file, In his early teens, he read Richard Alpert, Alan Watts, "all the Western Easterners," searching for God. He drifted to the existentialists, but finally decided that "if Camus is right and life has no purpose, then suicide really is the only alternative. The existentialists are dangerous," He tried LSD, "but that just let loose more questions."

By the end of his junior year, Hebel needed only one English class to graduate from his Long Island high school, He had already taken the SAT tests and chalked up two 800s, the highest scores possible, Cornell had already accepted him; counselors were pushing Harvard and Yale. And then he discovered ISKCON.

"It was ironclad, not guru-y sentimental or Judaic-Christian-arbitrary," Hebel says. "It made sense. I went for it."

Hebel moved into the New York temple, much to the dismay of his mother, who begged him to finish high school first. When the temple president suggested he marry a new devotee named Susan, he did,

Susan's father, an Oregon physician, had been killed in a car crash when she was in her early teens. Her mother married a second time, to a man Susan says was interested only in her mother's money, Her mother and stepfather started each morning with Bloody Marys and drank all day, Sickened by how empty life seemed, Susan went looking for a cause she could devote herself to and discovered ISKCON.

"ISKCON offered a surrogate family that often was better than the family devotees escaped," says Ellwood, "Its communalism fit in perfectly with the communal lifestyles that were in vogue at the time. Women are subservient in the Hare Krishna movement, which is hard to reconcile with the feminist, egalitarian movements that were also in vogue, but living in a very ordered society makes some women feel secure. They accept the role because they feel they are doing work of ultimate importance,"

Both Steve Hebel and Hansadutta played important roles in spreading ISKCON around the world. Hebel became ISKCON's recording secretary. Hansadutta helped open temples in Montreal, Vancouver, Berkeley and West Germany. When Prabhupada returned to India to preach in the mid-’70s, Hansadutta joined him.

"We were bigger than the Beatles in India, I swear we were," Hansadutta says. "People came by the thousands to see Americans in robes, shaved up and chanting. For centuries, Indians have been talking about taking their religion west. Here was proof that somebody had done it. Wow, what a sensation! Prabhupada could have been elected president of India."

Prabhupada died in Vrindaban, India, in 1977. He left a movement that had 126 temples in 47 countries (40 temples in the United States), thousands of devotees, and millions of dollars. New religions always face a crisis when a powerful, charismatic founder dies, Unfortunately, ISKCON did not produce a St. Paul.

"Prabhupada was a father figure, a moral authority, God's representative on earth," says Stilson Judah. "Without him, the movement had no moral or spiritual exemplar."

At a meeting in Vrindaban, 11 of Prabhupada's leading disciples carved the ISKCON world into kingdoms. Each became a guru; claiming a connection to Prabhupada and Krishna so pure, they should be worshiped as "transparent." Each demanded the absolute power over devotees that medieval kings had over serfs.

"They became 11 little Prabhupadas; but none of them were pure enough to succeed him," says Atreya Rishi, a former Berkeley temple president and a member of the Governing Body Commission that—in theory only —controls ISKCON. "They had no clear understanding of their own powers. Even God, who is absolute, does not interfere with individuals the way they do. They attempted to act greater than God."

"The people who started the movement were creative and free thinking," says Steve Hebel, "The gurus wanted blind sheep for followers, Nowhere in the scriptures does it say, ‘Become a dummy,'

"Ramesvar [Robert Grant, a guru who took over the Los Angeles temple] and I were initiated about the same time," Hebel continues, "As far as I was concerned, we were equals, Then all of a sudden, he's a god, I'm supposed to worship him and do everything he says, To me, he’s still Bobby Grant from Roslyn, N.Y. No way can I accept him or any of the gurus as spiritual masters."

Hebel did not become a blind sheep. He became a black sheep. When Prabhupada died, he and Susan and their three children were living in New Vrindaban, a 700-member, 3,000-acre commune in West Virginia that is the largest Krishna compound in America, It is the site of "America's Taj Mahal," the lavish Palace of Gold, built to honor the ISKCON founder. Slowly, steadily, Steve began to slip away from the movement. He started smoking, drinking and using drugs, He and Susan separated. He took a trip to India and came back with 10 kilos of hashish. More drug deals followed. In 1980, Steve Hebel was arrested in Canada with 70 pounds of marijuana he intended to distribute in the United States.

"ISKCON is a very austere life," Hebel says. "You are supposed to abstain when everyone around you is indulging. You break one vow and pretty soon you've broken them all. It all fell apart for me."

HEBEL ENDED UP SHOOTING HEROIN. Hansadutta got hooked on an even more powerful drug: power, He had done very well when Prabhupada's successors carved up the movement. From his base in Berkeley, Hansadutta governed the West Coast, 'Southeast Asia, southern India and Ceylon. He was worshiped as a perfect emissary of God who could do no wrong.

Hansadutta blames Jiva, the ex-con who was sleeping with and beating the women who were bringing thousands of dollars into the Berkeley temple, for turning him into a leader who could do nothing right.

"Jiva ruined his life, and he ruined me, too, because I had to undo what he'd done," Hansadutta says, "I got entangled with Nadia, one of Jiva's women. She was an extremely intelligent, talented artistic woman with a tremendous amount of energy. I fell down, broke my vow of chastity.

"I was shattered," Hansadutta continues. “I couldn't sleep; I had headaches all the time; I started taking codeine and percodan and drinking alcohol. I lay in a dark room for months. I was going to commit suicide; it was only a question of how. Guns? A car? Jump off a bridge? I became infatuated with guns."

With Prabhupada gone, there was no one around to stop Hansadutta’s slide into chaos. Dozens of people obeyed his every command as if the dictates came directly from God, They were not about to say, "Hansadutta, you are screwing up."

"ISKCON leaders have such tremendous power, if they burp, it’s considered holy," says Peter Chatterton, whose Krishna name is Bahudak. Chatterton was an ISKCON regional secretary and Vancouver temple president from 1972 until he left the movement last winter. He and his temple stayed above the fractious disputes and criminal activity that have devastated ISKCON.

"Under the gurus, the supreme virtue in ISKCON became surrender," Chatterton continues. "The dominance-submission went all the way down the line. The guy who had been in the movement six months expected subservience from new devotee. You were supposed to surrender everything—your thoughts, values, actions, your whole life—to the next guy up the ladder."

Hansadutta gradually evolved from "secretary to God" to "gum with a gun." At his command, devotees began carrying weapons in Berkeley and stockpiling an arsenal at Mount Kailasa, the sect's 400-acre farm in the Maycamas Mountains in Lake County.

The transition from Krishna-worshiping holy man to gun-carrying survivalist is not as bizarre as it may seem. Prabhupada, the ISKCON founder, abhorred Western society, considered it materialistic and spiritually void. He created a separatist movement of Krishna monks who would remain uncontaminated by Western values. Eventually, they would become role models for the karmies, who Prabhupada believed would come to their senses and join ISKCON in droves.

Hansadutta simply added a paranoid element to the founder's teachings. In his version, the karmies weren't going to join ISKCON; they were going to try to destroy it before they destroyed themselves in World War III. Hansadutta saw the world as Us against Them, the pure against the corrupt.

"The appeal of religions visions like Prabhupada’s is that they create a divine melodrama," says Mark Jurgensmeyer, a professor of religion at UC-Berkeley and the Graduate Theological Union. "The vision creates a world of absolute purity that challenges the moral limitations of the normal world. It's tremendously exciting. People feel they are involved in a battle where ultimate issues will be decided. Once you feel that way, violence is justified. Your vision is so pure, you will do anything to tip the world in your favor,"

The guns, the submissive women, the big money coming off the streets, attracted criminals like flies to a rotting orange. "At one time, a large number, if not the majority, of people in the Berkeley temple had arrest records," says Joe Sanchez, a Berkeley police officer who became an expert on ISKCON while arresting 60 devotees during the past six years. "It's kind of amazing when you've got a church where everyone has been booked at least once,"

According to Sanchez, Hansadutta honed his shooting eye by taking pot shots at devotees on the Lake County farm. Sanchez says he hit a 5-year old boy in the hand.

According to Sanchez, Hansadutta honed his shooting eye by taking pot shots at devotees on the Lake County farm. Sanchez says he hit a 5-year old boy in the hand.

"Spencer Lynn Joy, the acting president of Mount Kailasa, came forward and said the shooting was his fault," Sanchez says. "But when I talked to him, I was told by Mr. Joy it was Hansadutta who shot the boy. If I could find Mr. Joy, I believe he'd tell me again who fired the round at the child. I have been looking for Mr. Joy for three years. He has disappeared. He has not been in contact with family or friends."

"I never took pot shots at people," Hansadutta counters. "A bozo devotee was cleaning a gun. It fired accidentally, went through a trailer and hit a kid,"

Hansadutta looks back on the past with little emotion, as if it happened to someone he once knew but has lost touch with. He is 46 today, has a deeply lined face, and is missing the teeth behind both incisors. His Western name was Hans Kary until be changed it to Jack London. He didn’t change it because he admired the novelist. He changed it because he used to take entourages on first-class trips around the world.

"Every time I'd' go through customs in places like Bangkok, I'd get hassled because l had a foreign name and an American passport," he says. "I got tired of it. I used to pass Jack London Square on my way to the airport. I liked the name. It was simple, easy to remember. I'd never read one of his books."

Devotees who still defend Hansadutta are quick to say, "He might have messed up, but lie published a lot of Prabhupada's books." The energetic Hansadutta did publish the ISKCON founder’s books, by the thousands in Singapore. Most of the money for the books, the trips, the guns, the expensive property in Berkeley and the farm in Lake County, came from devotees working scams on the streets.

Instead of dressing in robes and trying to sell Krishna literature, as they bad once done (a practice known as sankirtan, or spreading the faith), the devotees wore Western clothes and claimed they were collecting for charities that did not exist. All over America, devotees have posed as Vietnam War veterans and as Catholics collecting for Catholic charities. Over the three-day Labor Day Weekend, they say they are collecting for Jerry Lewis' telethon.

"In L.A., they dress up as Santa at Christmas and stand on street corners ringing bells," says Steve Hebel. "There's hundreds of Santa suits hanging in a room in the L.A. temple. They look pretty weird in an Indian temple."

Hansadutta and a lieutenant augmented the charity ruses with one of the more inventive scams in the history of street hustles. They heard about warehouses in Los Angeles where they could buy cutout records (albums that had not sold) for five or 10 cents apiece, The Krishnas bought cutouts by the ton. They loaded the records into vans and parked on street corners and in shopping centers. Then they held a dead microphone and stopped people with "Excuse me sir, we're from radio station KSNA [i.e, Krishna]. Where are you from? San Francisco? That's terrific! What kind of music do you like? Rock 'n' roll? Well, it's your lucky day! We're passing out free albums today! Here you are, here’s three rock 'n' roll albums. How about that!"

Once the person who thought he was on the radio accepted the records, the hook was in.

"We'd say we were running a campaign to fight hunger in Africa or were collecting for muscular dystrophy; we'd tell them anything," says Bill Costello, a former Berkeley devotee who worked the scam all over the country. "People felt good, they had the albums, and they'd give $5, $10, $20. We always had a big wad of ones we used to quick-change people. There was more money coming in than you’d believe—I'd say $2,000 to $10,000 a day—and it all went to Hansadutta."

The guru estimates that between $25,000 and $30,000 of that money to make four rock 'n’ roll albums starring himself.

His song, "Guru Guru on the Wall," begins with a machine gun burst. The chorus is "Guru guru on the wall/ Who is the heaviest of them all?/ Whose disciples are the worst?/ Who could I give my last shirt?"

"It was another way to preach," Hansadutta says. "America was so absorbed in rock 'n' roll, I thought it might be a way to reach people, I got a little puffed up."

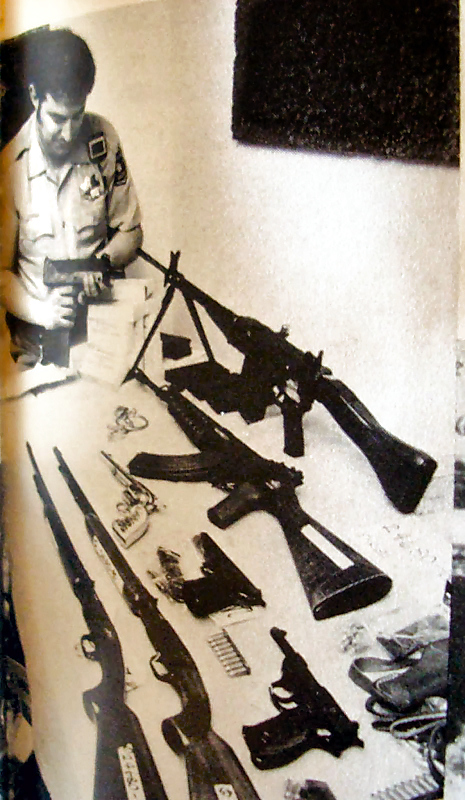

Photo left: Berkeley police officer Joe Sanchez Inspects the weapons police discovered in 1980, when they searched an unregistered Mercedes parked at the home of Hansadutta, then the Berkeley temple's guru.

Photo left: Berkeley police officer Joe Sanchez Inspects the weapons police discovered in 1980, when they searched an unregistered Mercedes parked at the home of Hansadutta, then the Berkeley temple's guru.

POLICE RAIDED THE KRISHNA FARM IN LAKE COUNTY in March 1980, finding among other weapons a grenade launcher, four short-barrel shotguns, and thousands of rounds of ammunition. Later that same month, police raided a Krishna-owned warehouse in El Cerrito that held enough casings, slugs and gun powder to make 50,000 rounds of ammunition.

Acting on a warrant two months later, the Berkeley police searched a car and found an Ingram submachine gun, two military assault rifles, three loaded pistols, a Walther P-38, a 9mm Browning, a Colt ,45 and a commando-style 9mm automatic weapon, The car, an unregistered Mercedes, was parked in the driveway of Hansadutta's Berkeley home, The ,45 was registered in his name. The guru was arrested and charged with, among other things, possession of an automatic weapon, a federal offense. He beat the charges when a devotee claimed ownership of the weapons.

The brushes with the law did nothing to cool down Hansadutta. He kept collecting weapons, running his street scams, and publishing Krishna books. And Joe Sanchez kept arresting his followers. The Krishnas finally hung a picture of Sanchez in the temple above a sign that said, “This man hates you,"

And then, one August night in 1984, Hansadutta ran amok.

Shoppers in Ledgers Liquor Store on University Avenue in Berkeley must have thought they were in a Sylvester Stallone movie. Bullets blasted through the front window, shattering whiskey and gin bottles on the shelves. Shoppers hit the floor, When the gunfire stopped, somebody outside floored a Ford Bronco.

When the cops pulled the Bronco over, Hansadutta stumbled out, drunk on ouzo. He had just fired 18 shots through the windows of McNevin Cadillac on San Pablo Avenue. The cops found a 12-gauge shotgun, a 9mm pistol, a semi-automatic ,22 pistol and a fully automatic 9mm machine pistol, plus box after box of ammunition. The weapons were loaded; the guru was carrying $8,200.

“I was totally in despair," Hansadutta says. “I didn't know which way to turn. I was like a kid throwing rocks through windows in frustration.” The guru got off with what cops derisively call “post card probation"—all he was required to do was inform a probation officer of his whereabouts once a month for three years and pay $5,000 restitution. The ISKCON Governing Body Commission, which had done everything it could to keep Hansadutta in the movement, finally had to excommunicate him.

“I was crushed," Hansadutta says. "I always saw my future in the movement. By myself, what could I do?"

DEVOTEES COMPARE ISKCON POLITICS TO A TURTLE TANK—somebody is always trying to climb up on someone else's back. Hansadutta decided to fight for control of the Berkeley temple, He formed an alliance with the biggest ISkCON turtle of them all, Kirtanananda Swami Bhaktipada. Kirtanananda (pronounced Kir-ton-a-nonn-da), the most powerful ISKCON guru, built New Vrindaban and the Palace of Gold in West Virginia. In January 1986, Hansadutta and Kirtanananda tried to take over the Berkeley temple.

"They sent 15 men out here and took $150,000 worth of cars, books and deity paraphernalia and left us with nothing,” says Atreya Rishi, who succeeded Hansadutta as guru in Berkeley. “We got a court injunction, but that didn’t stop them. Kirtanananda kept writing, advising me to surrender the temple to him. When I saw there was no end to their aggression, I filed a lawsuit.”

“I could have taken the temple anytime I wanted it,” Hansadutta counters. "I could have sat on the guru's chair and smoked a cigar and drank a glass of wine, and they would have signed it over to me. That’s how much the devotees were committed to me."

Why would anyone who joined ISKCON to find spiritual enlightenment follow Hansadutta through all the scams and guns?

"Devotees lose their personal identity as time goes on,’’ says Ellwood. “The movement is your life’ gets reinforced over and over. They identify so completely with it, they lose all sense of self. There's nothing else in their lives,"

"The same sick thinking that affected the gurus is present in many devotees," adds Peter Chatterton, the former Vancouver temple president. "A lot of them see themselves as the elect, as spiritually advanced. They look contemptuously at other people. They lack self-perception and can't see their own faults. Most of all, they lack human kindness."

In early 1986, Hansadutta withdrew from the battle for the Berkeley temple and checked himself into a drug- and alcohol-treatment program.

"I was drinking a lot, and I became addicted to Halcion [a powerful sleeping medication]," Hansadutta says. "I rented an apartment near the Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic and went through their program."

When Hansadutta graduated from the drug program and reconnected with his followers, they were full of stories about a devotee named Steve Bryant, Bryant, they told Hansadutta, was living in a van on the streets of Berkeley. He was writing an expose of the ISKCON gurus, He was telling everybody the gurus should be killed, "The penalty for false teaching is death," Bryant wrote. "It is only a matter of time before each 'guru' is dead."

Hansadutta set up a meeting with Bryant, Bryant was scared. He walked into the meeting carrying a loaded .45

"We met for two hours," Hansadutta says, "He said if the pages he was distributing didn't have an effect, he was going to kill Bhaktipada [Kirtanananda], "I asked him, 'Do you follow the principles? [No meat, no intoxicants, no gambling, sex only for procreation.] He said he smoked pot. I said, 'Then what is the use of you writing all this stuff? You have no validity. First make yourself perfect, then criticize. Stop all this nonsense.' "

Bryant did not stop. He eventually took his campaign public, telling cops, journalists, anyone who would listen, now the gurus had corrupted ISKCON. Nobody except Berkeley police officer Joe Sanchez paid much attention.

"I knew most of what Bryant was saying was probably true," Sanchez says, "It was frustrating because as a local cop, there's not much I can do about crimes that are international in scope. I passed information along to various federal agencies, but it disappeared into a black hole. I heard nothing back,"

BRYANT'S CHARGES OF CHILD MOLESTATION, murder, the abuse of women, and international drug trafficking were so horrid, they were easy to disbelieve. Besides, without hard proof like incriminating documents, it is easy to dismiss people like Bryant as "kooks." Cops have to be very careful when they investigate religions, particularly esoteric religions like ISKCON, because they open themselves up to all kinds of First Amendment problems. It is also bard work. To do a good job, investigators have to learn almost as much about the religion as its follower's.

Like cops, journalists are quick to dismiss people like Bryant as kooks. The first thing they do after hearing stories as hair-raising as Bryant's is call people in law enforcement, If the cops can confirm the allegations, it's a story. If they can’t, it’s not.

Over the past 10 years, there have been occasional investigations into the Krishnas' illegal activities. Sporadically, stories have been written about crimes committed by members of the sect. But generally, cops, journalists and the public continued to think of the Krishnas—if they thought of them at all—as a benign if strange relic of the '60s.

To gain credibility, Bryant had to die. On May 22, 1986, he was dead, shot twice in the head while sitting in his van on a dark street in Los Angeles. Bryant's death started the separate but overlapping investigations that are now going on all over the country. If he hadn't been killed, the crimes that are now being uncovered might have stayed buried deep in the Krishna movement.

"Steve Bryant is a true martyr," says Joe Sanchez, the Berkeley police officer. "He died to clean up his faith."

NEXT WEEK: How Bryant's campaign to keep his wife from divorcing him led to a crusade against the ISKCON gurus, and how his death triggered investigations that are shattering a religion that once promised to unite East and West.

(JOHN HUBNER is a staff writer for West.)